Sustainable Design is all about broadening our perspective—beyond simply product specifications or user requirements to

how a product contributes to a more sustainable environment over the course of its life: from its creation and use to its death and disposal. By thinking of this process as a cycle, it becomes clear that even the smallest sustainable design choices made along the way can result in large savings of both waste and energy.

The

"Sustainability & Design Series" explores the impact of the sustainability movement on product design, user experience, and how companies do business. It is based on insights from the book

User Experience in the Age of Sustainability by Senior User Experience Designer

Kem-Laurin Kramer. This third post in the series will examine

Product Life-cycle Analysis as an approach to more sustainable design.

Broadening our Perspective

This approach to sustainable design is different from the others in that it aims for a holistic understanding of the product and the system within which it operates, rather than a simple, clear solution (as Biomimicry and Dematerialization might).

It forces designers to get out of their product bubble and get a much broader perspective on the impact that the design choices they make will have on the system as a whole. This approach also makes it easier to influence and track change by breaking down the areas to be examined into distinct phases: manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal. The structured approach means that it's much easier to measure the progress that is being made within each stage. As Kramer writes: It "enables the quantification [of] how much energy and raw materials are used and how much solid, liquid, and gaseous waste is generated at each stage of the product’s life."

Ultimately, a Product Life-cycle Analysis comes down to

a cost-benefit analysis of all the factors that going into making, moving, and using a product. The "cost" can be defined as waste, which must be minimized, and the "benefit" can be defined as energy savings, which must be maximized. The goal is "to extract the maximum practical benefits from products and generate the minimum amount of waste possible as part of the design output."

When viewed in this way,

many product designs that we may have originally viewed as sustainable in one context, may not be so when observing the entire context of its life-cycle. For example:

- When factoring in the energy and processes required to make them, plastic bags generate 39% less greenhouse gas emissions, consume less than 6% of the water necessary to make them, and consume 71% less energy when making them compared to paper bags

- Although bamboo is regularly promoted as a sustainable and organic material for clothing and flooring, most bamboo is processed as bamboo rayon, which undergoes much toxic and chemical processing in order to change from plant to useful fibre.

Below are the four stages of the Product-life Cycle, areas that designers should consider within each, and a few examples of sustainable design.

Phase 1: Manufacturing

Key questions to consider:

- What materials are the products made from?

- How were the materials extracted?

- Does the product contain hazardous materials?

- Was the product manufactured under ethical conditions in the extraction and manufacturing process?

Herman Miller Mirra chair

This office chair was designed to accommodate both the sitter and the environment in its design. Launched in 2003,

it was developed with a design protocol rooted in recyclability, reduced toxicity, and renewability, and it is made of 96% recyclable material. The chair can also be disassembled in less than 20 minutes, which means that it is serviceable as well. Part of what led to the design of the chair was the company's all-encompassing examination of its product line's “materials chemistry”, during which it catalogued every material in every product.

Phase 2: Transportation

Key questions to consider:

- What transportation costs (emissions) are associated with the product’s production?

- How is the product packaged?

- What are the packaging constituents?

- Is associated documentation produced as part of the out-of-the-box experience?

- Are products compactible to lower transportation emissions and cost?

Apple MacBook Packaging

Apple claims that, by reducing its packaging of the MacBook by 53% between 2006 and 2010, it shipped 80% more boxes in each airline shipping container, which saves one 747 flight for every 23,760 units shipped.

Adidas' Shipping Policy

Adidas’ policy is to rely on transportation methods that use less energy, like ocean freight (as opposed to air freight). “Our policy is to minimize the impacts from transport, in particular minimizing air freight shipments. Generally, we plan to ship products by ocean freight.”

IKEA's Sustainable Transportation Initiatives

IKEA has created pilot programs for environmentally friendly home delivery services as well as providing free shuttle bus service to and from its stores. In Denmark, customers can even borrow bicycles with trailers to bring their purchases home.

Phase 3: Usage and Energy Consumption

Key questions to consider:

- How much energy is consumed during the use of the product?

- Does the product engage users in allowing some active management of energy preservation?

- Does it provide energy usage management guidance as part of the out-of-the-box experience? (ie. A smart usage guide)

- What is the performance of the product?

- What are the user’s perceived and real experiences with the product?

- What is the user’s perception of the ecological value of the product, its durability?

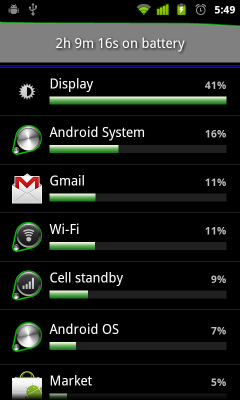

Android's Power Management Screen

For example, with Android's mobile phone software, the system can use data collected while a user is actively using a device and to educate them about specific opportunities to save power.

Phase 4: Recyclability (Reuse and Dematerialization)

Key questions to consider:

- How long does the product last?

- Do users think that the products are durable?

- If broken, can the user repair the product easily, is it serviceable?

- Can the constituent parts of the product be broken down to create other products?

- Are there alternative service subscription options to the product?

- Are the necessary parts available locally?

Maille Mustard's Specialty Jars

Maille has taken a sustainable approach to the design of their jars: after use, they can be used to hold anything from liquor to candles. As Kramer notes, selling their products in packages with longevity also provides “stickiness” for the brand by: it becomes part of their living environment long after the actual product has been used up.

Pizza Hut's Smart Box

In Costa Rica, Pizza Hut introduced multifunctional pizza boxes, which can be separated into individual plates and a small container for leftovers. This eliminates the need for disposable plates and extra storage materials like aluminum foil and plastic wrap.

Value Perception and the Product Life-cycle

One factor in product design (not to mention brand positioning and communications) that has a major influence on how consumers approach, interact with, and dispose of products is their pre-existing value perceptions.

This perception starts, of course, with the brand's associations. For example, automotive brands like Toyota and Volvo already have associations ("reliability" and "safety/durability" respectively) that tell consumers that they'll be using the cars for a long time. Brands like Chevrolet and Ford, which have struggled in recent years (although they are getting better at changing these perceptions), were only expected to last for a few years.

Communications and demonstrations can also play a role in how consumers use, and eventually discard of, a product.

Commercials, videos, or marketing materials can educate consumers on how to treat products during their life-cycles before they've ever used it. In-store (or online) demonstrations can do the same. By the time consumers actually begin to use the product, these pre-existing notions have already been built in, and will either be reinforced by or negated by the product's design.

Finally, the materials selected during the manufacturing phase have an impact on the value perception of the product. (Above, materials were only discussed in the context of their environmental impact.) As Kramer writes: "Perceived value plays an integral part in the design process when it comes to such activities as selecting materials.

Some materials have an intrinsically high perceived value. For example, metal and glass as more valuable than plastic, silver is more valuable than copper, and so on. The eventual goal is waste reduction, because when customers feel that something is more valuable, they are likely to retain it for longer periods."

The final approach to sustainable design that will be discussed in the fourth post of the "Sustainability & Design Series" is called Dematerialization. Stay tuned!

.jpeg)